This document is for experienced software engineers who already know several other programming languages and just want a TL;DR summary on JavaScript in the context of React, Flow and the new ES6+ hotness.

20 seconds of history

JS has been designed and implemented in 10 days around 1995. It had (and still has) a bunch of weird quirks. All major browsers adopted it and JS spread like wildfire, but everyone had their own opinions on how it should work. In 2005 the spec became open standard (ECMAScript, or ES). In the recent few years the work on the standard gained a lot of momentum.

Also in recent decade web pages became more and more complex, to a point where some of them turned into “web apps”. This increased demand for JS.

Basics

JS is a single threaded, dynamically typed, functional programming language. It’s not the best one out there, but it’s okay.

JS is often associated with web, but it’s a generic scripting language. Browsers make some of their features controllable from JS via DOM, NodeJS exposes various UNIX APIs to JS, etc.

Syntax

JS belongs to C/Java family. It’s easy to pick up from examples, the more nuanced edge cases will be discussed here.

Variables and types

const foo = 5;

let bar = "hello";

bar = bar + ", world";

Note that const prevents re-assignment of the variable, however if the value is a mutable object or array it can still be changed.

Basic types:

- numbers (52-bit):

0,42.24,0xf00,-Inf/+Inf(infinity),NaN(“not a number”, the irony!) - strings:

'single quotes'and"double quotes"are equivalent,`template literals let you use ${expressions} inline` - booleans:

true,false - arrays:

[],[1, 2, 'str', null] - objects:

{},{a: 1, b: 2},{"keys are always strings": {nested: [1, null]}(literally JSON). - functions: see below.

nullandundefinedare special unicorns, see below.

ES6 introduced a bunch of specialized collection classes, e.g. Map, WeakMap, Set, etc.

null vs undefined

null used to mark empty value, undefined used to mark that there is no value. For example:

const list = ["apple", "banana", null];

list[0]; // 'apple'

list[2]; // null

list[9]; // undefined

If it doesn’t make sense, forget about this for now. Don’t think about it. It will “click” when it’s time.

Equality and “truthiness”

To compare values, always use ===. Pretend == does not exist. Objects and arrays are compared by reference, not by value, so {} !== {}.

0, '', false, null, undefined, NaN are considered falsy, everything else in boolean context is true.

Functions

Functions in JS are first class, i.e. you can use them the same way you use any other value – assign to variables, add to arrays and objects, pass as arguments to other functions, etc.

const square = (x) => x * x;

console.log(square(5));

// 25

If a function contains more than one statement, use curly braces and explicit return statement:

const squareAndLog = (x) => {

console.log(`Called with x = ${x}`);

return x * x;

};

There is another way to define a function:

const oldSchool = function () {

console.log("hello, world");

};

but it has unintuitive behavior when it comes to dynamically-scoped this (see below), so prefer arrow functions.

Objects

Object is a very common data structure in JS. In essence it’s a bag of key-value pairs. Keys and values can be anything, but usually keys are strings. If key is a string that can be valid identifier (e.g. no spaces and special characters) quotation is omitted.

const myCat = {

name: "Peanut",

owner: {

name: "Bob",

},

"stuff it likes": ["milk", "butterflies"],

jump: () => {

console.log("jumped");

},

};

myCat.name; // Peanut

myCat["stuff it likes"]; // ['milk', 'butterflies']

myCat.jump(); // jumped

Before introduction of specialized collections, objects were often used as maps or sets. Now there are dedicated Map and Set classes.

OOP

JS uses prototype inheritance. Every object has a magic hidden property called __proto__. When you access cat.color and cat doesn’t have color key on it, JS runtime will check if cat.__proto__ has color, then cat.__proto__.__proto__, etc. until found, otherwise returns undefined. Read more about prototypes.

You can explicitly check if an object has specified key using foo.hasOwnProperty('bar') or get a list of all available properties via Object.keys(foo).

It’s a powerful system, but it confused shit out of people and everyone was rolling their own implementation of inheritance. So ES6 introduced more conventional class syntax (still uses __proto__ under the hood):

class Cat extends Animal {

constructor(name) {

super();

this.name = name;

}

say() {

return `${this.name}: meow`;

}

}

const peanut = new Cat("Peanut");

console.log(peanut.say());

// Peanut: meow

Inside functions this is a magical variable that points to “the object that the method was called on”. For example when calling peanut.say(), inside say method this will point to peanut.

However, if you do this:

let catsay = peanut.say;

catsay();

it will fail because this will be undefined. To make the function “remember” the instance it was called on, use bind method of the function (functions are also objects, surprise!):

let catsay = peanut.say.bind(peanut);

catsay();

It returns a new function that knows what this should be. You can bind functions to any value, not just class instances.

It’s a very common source of errors.

JSX

JSX is syntax sugar introduced by React to make it easy to describe complex view hierarchies. It’s not required, but it saves developers from the “closing parenthesis problem)))))”

const view = (

<div className="test">

<span>hello world</span>

</div>

);

is equivalent to:

const view = React.createElement(

"div",

{ className: "test" },

React.createElement("span", null, "hello world")

);

name="value" pairs are called attributes (or props). Strings should be wrapped in double-quotes. To insert a JS expression into JSX, wrap it in curly braces:

<div className={styles.main}>Next value is: {x + 1}</div>

Every element can have zero or more elements inside (called children). There is a shortcut that can be used for empty elements:

<Profile user={me} />

JSX elements are values, so they can be stored in variables, arrays, returned from functions etc.

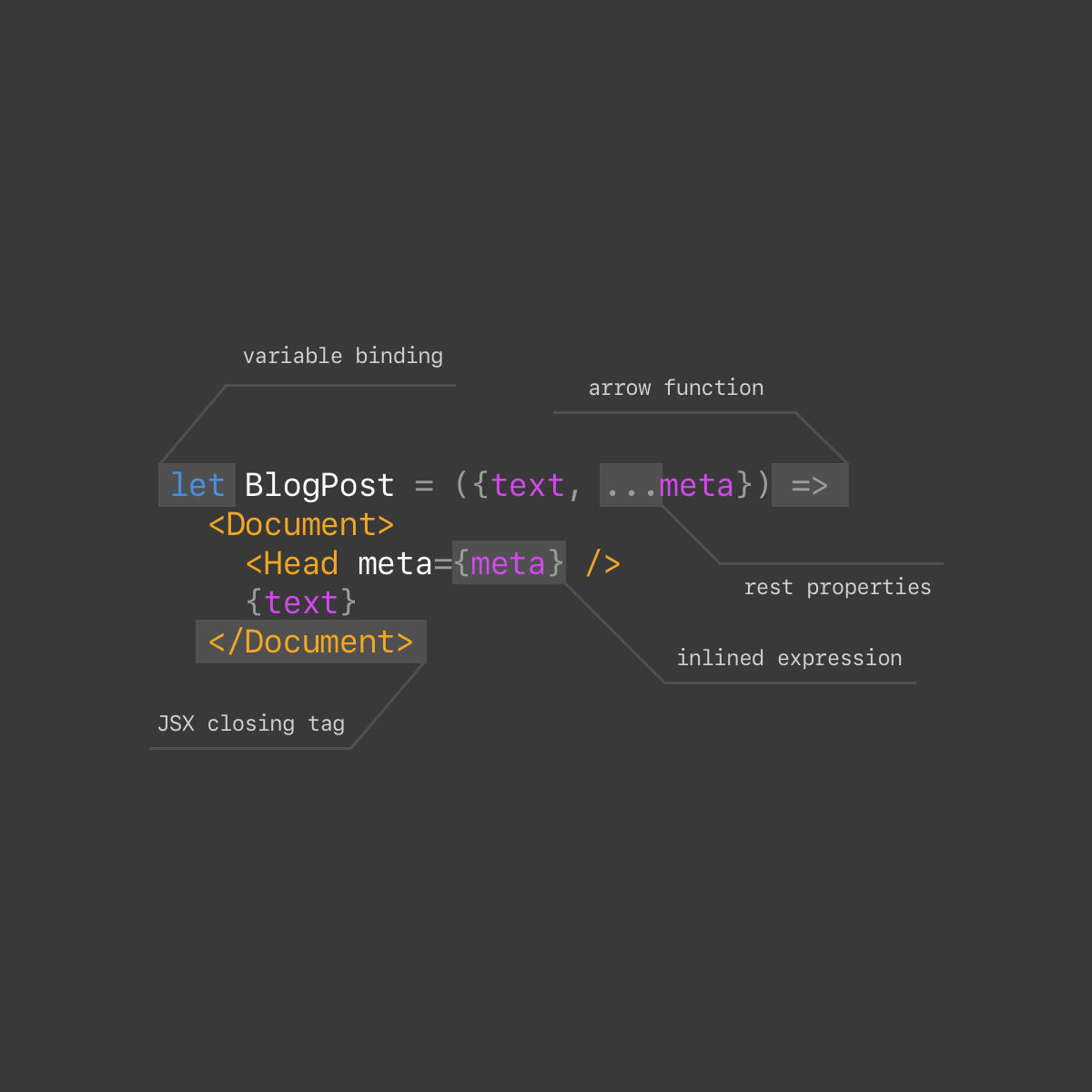

Destructuring and spread

There are a bunch of other nice syntax features that make using JS more fun.

Destructuring lets you extract several values from JS data structures in one line of code:

const catData = { name: "Peanut", age: 3, owner: "Bob" };

const { name, age } = catData;

// now name === 'Peanut', age === 3

You can think about spread operator as “insert values” from one object or array into another

const alphabet = ["A", "B", "C"];

const characters = ["1", "2", ...alphabet, "~"];

// characters = ['1', '2', 'A', 'B', 'C', '~'];

it can also be used in context of function definition and calls, for example:

const sum = (...args) => args.reduce((e, a) => e + a, 0);

sum(1, 2, 3); // 6

const arr = [10, 20, 30];

sum(...arr); // 60

Destructuring and spread can be used together:

const list = [1, 2, 3, 4];

const [head, ...tail] = list;

// head = 1, tail = [2, 3, 4];

Transforms

There are lots of new features in the standard, and not all runtime vendors can deliver them fast. There are also controversial things like JSX that are unlikely to get to the JS standard committee.

It became a very common practice to use tools that take source code written in new syntax and produce code compatible with old syntax. Most popular tool that does that is Babel.

Polyfills

Not all new features can be transformed. Sometimes standard adds new properties to existing classes, e.g. String.startsWith. Polyfills are small pieces of code that in runtime detect if these methods are available, and if not, mocks the implementation.

Async

JS is single-threaded and traditionally used for event-based scripting, e.g. “when user clicks this button, show alert”.

There are no blocking operations in JS. If the code needs to fetch a web page, for example, it can’t just block and wait for the value, and should supply a callback instead. Obviously it influences the control flow, so be careful:

console.log("Before fetch");

fetchURL("https://facebook.com", (response) => {

console.log("Got response");

});

console.log("After fetch");

// Before fetch

// After fetch

// Got response

In real world app callbacks get out of hand very quickly:

const loadAndStore = (callback) => {

fetchURL("https://facebook.com", (response) => {

response.loadBody((body) => {

db.save(body, () => {

callback();

});

});

});

};

Promise is a value that represents async operation and lets you attach and chain handlers:

const loadAndStore = () =>

fetchURL("https://facebook.com/")

.then((response) => response.loadBody())

.then((body) => db.save(body));

New async/await syntax makes it even easier to use promises:

const loadAndStore = async () => {

const response = await fetchURL("https://facebook.com");

const body = await response.loadBody();

return await db.save(body);

};

Future

Whenever you like it or not, JS is everywhere now: web, mobile, server, smart devices, etc. However, you don’t have to use JS directly – lots of languages (including newer versions of JS) consider JS as compile target.